TINY

FISTS: INTERVIEWS WITH FOUR FORCIBLY CONSCRIPTED BOY SOLDIERS OF THE BURMESE

ARMY

By Saw Takkaw

August 2003

“Burma’s army

preys on children, using threats, intimidation and often violence to force

young boys to become soldiers. To be a boy in Burma today means facing the

constant risk of being picked off the street, forced to commit atrocities

against villagers, and never seeing your family again.”

- Jo Becker, Human Rights Watch

The nation of Burma is a human disaster zone. Future historians, no doubt,

will place the Burmese military dictatorship (SPDC) on the same despicable

page as the Khmer Rouge and the regimes of Ceausescu and Amin. Reflecting

upon the horror that constitutes today’s Burma, future generations, scholars,

and those who agonized under SPDC rule will most certainly utter the timeless

and fatigued question, “Why?”

But presently, we in the field of human rights documentation watch with growing

consternation as the mountainous stacks of reports on human rights violations

from Burma grow shamefully higher. These piles of reports, photographs, and

interviews that were meant to wake up the world to the situation in Burma

and act as a voice for its victims have instead formed makeshift, impromptu

memorials to a nation that has suffered over forty years of brutal military

rule. The four lives discussed in this report add yet another thin layer to

that now massive heap.

In the last fifteen years, the SPDC has doubled the size of its army, making

it among the largest in Southeast Asia. In its desperate struggle to maintain

power, the ruling generals of Burma are attempting to mold the peoples of

Burma into a solid fist - a fist not to defend against outside attack or invasion,

but to achieve total domination of the peoples of which the fist is composed.

The SPDC’s intense drive toward militarization has left thousands dead

and maimed, hundreds of thousands internally displaced or in refugee camps,

and millions living in poverty and fear. The four boys discussed in this report

are among the human wreckage, the “trampled grass” of this institutionalized

barbarity.

I would like to also comment on the treatment the subjects received from those

they surrendered to, the KNU (Karen National Union). For the most recently

surrendered youths, I was contacted by a KNU battalion commander, who asked

if I would approach the relevant humanitarian agencies on their behalf. On

several occasions I also observed the boys while they were with the KNU. I

found them to be decently fed, clothed, and treated. They were not held under

confinement. Judging by the fact that I had just previously visited a Karen

IDP (internally displaced persons) site, where numerous Karen children were

suffering from malnutrition, I must doubly salute the KNU’s care of the

subjects of this report.

Lastly, this study is a salute to its young subjects, four boys, who at great

risk threw down the gun that had been forced into their hands. It is now the

responsibility of the international community to provide aid that will fill

their empty hands and to take an active role in rebuilding their shattered

lives.

In order to avoid repetition, consistencies in the subjects’ reports

that do not provide additional information into the nature of each specific

case are listed below. The reader should also note that the subjects were

interviewed individually.

1. All of the subjects were forcibly conscripted. It is important to note

that the subjects of this report were not drafted, but were arbitrarily arrested

and pressed into military service.

2. Although none of the subjects ever engaged in combat, they all received

combat arms training and were issued and carried weapons in the field.

3. The subjects received little if any political indoctrination while in training

or on active duty. The subjects were conditioned, however, to obey military

authority unconditionally.

4. The subjects were told by their training officers that if they were captured

by “the insurgents,” they would be tortured and killed.

5. The subjects were in combat arms training for approximately four and a

half months (although some were interned in holding centers while waiting

for the class size to reach an acceptable number to commence training).

6. All of the subjects were sent to frontline units in Karen state.

7. All subjects held the rank of rifleman (lowest enlisted rank) or the equivalent

thereof in the Burmese Army.

8. All of the subjects fled from their units and surrendered to the Karen

National Union.

9. All of the subjects, save one, served in the Burmese army for less than

one year.

10. All of the subjects asserted that they had great difficulty carrying their

prescribed loads (e.g., rifle, web gear, backpack, ammunition, and mortar

rounds), and that they found the equipment to be oversized and unwieldy.

11. All of the subjects asserted that they had not been fed adequately while

in training or on active duty.

12. All the subjects stated that they had no contact with their families while

in training, but were permitted to see their families briefly after the graduation

ceremony.

*All subjects were presented by this writer with a copy of the UN Universal

Declaration of Human Rights (in Burmese).

1. “I am my parent's only son.”

Maung Y

Age: 14

Ethnicity: Burman

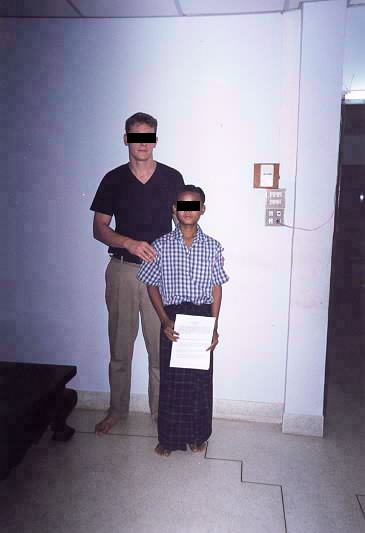

Maung Y standing next to the author. The boy’s small stature clearly

demonstrates his physical unsuitability for military service.

Maung Y was returning home after attending an evening tutorial class when

police in uniform and in civilian clothes seized him. They informed him that

he was being arrested for “loitering in the dark.” Maung Y was then

taken to a military camp for combat arms training, where he estimated that

over half of the recruits that he saw were under the age of 16. His class

was composed not only of ethnic Burmans, but also Shan, Karen, Mon, and Tavoyan

peoples. Nothing less than total and unquestioning obedience was demanded

of the recruits. This sterling rule was reinforced with beatings, which Maung

Y claimed he received often. The diet in training consisted of rice with small

portions of beans, eggs, or watery beef soup. The eggs served to the recruits

were sometimes rancid causing many to have dysentery. He also stated that

some of the young recruits became ill and subsequently went blind. (It is

unclear why. Perhaps it was due to protein deficiency or the intake of certain

medicines.) Maung Y claimed it was possible for parents to buy back their

children from the army, provided it was before graduation. Unfortunately,

Maung Y’s parents are poor, and he believed that they had no idea of

his whereabouts until shortly before his graduation from training. At the

graduation ceremony he saw his father who was very sad but could do nothing

about his son’s situation.

Maung Y was then sent to the Karen front. Weighing only ninety pounds, he

had to shoulder forty pounds of military equipment, including a rifle, web

gear, and ammunition. Marching in the steep hills of Karen state, he was expected

to keep pace with the adult troops despite his age and small body size. On

one occasion, Maung Y and his fellow soldiers were given a drink of special

army rum just before a strenuous march. He claimed that after drinking special

army rum, which differs from the army rum often issued to Burmese troops,

he and the other soldiers “had energy and were resistant to all pain.”

He also heard that special army rum was administered to troops just before

assaults on enemy positions.

Maung Y spent only one month on active duty before he escaped. During that

time, he saw prisoner porters, who were carrying heavy loads in the mountains

for the army, beaten by troops. His NCO’s (noncommissioned officers)

gave him extra duties, humiliated him with insults, and slapped him constantly.

Shortly before his escape, he was slapped and beaten by an NCO for cooking

more than the allotted rice ration for his boy soldier comrades. “We

were never given enough food,” he stated.

2. “I think what happened to me was unjust.”

Maung K

Age: 15 (conscripted at age 12)

Ethnicity: Burman

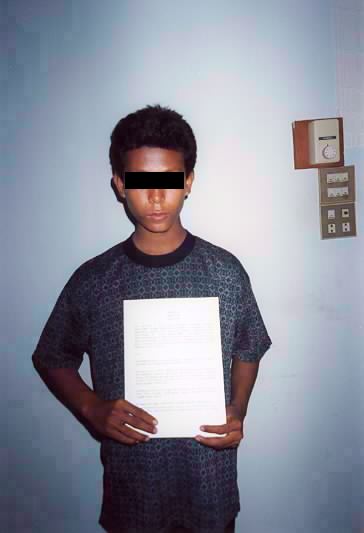

Maung K holding a copy of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (in

Burmese language).

Maung K was waiting at a bus stop (during daylight hours), when he was seized

by soldiers. The soldiers told him he could either join the army or go to

jail. He was interned in a holding camp for four months because there were

not enough recruits to start training. In training, beatings were frequent

and the recruits were told that anyone who opposes the government is a thaung

jan thu (terrorist).

After training, he was sent to a front line unit in Karen state. He figures

there were about thirty underage soldiers in his battalion (numbering two

hundred men).

At age 12, he was issued one bottle of army rum a week. Maung K found it extremely

difficult to bear the weight of the military equipment that was issued to

him. In the field, he saw prisoner porters, who carry food and other provisions

for the army, being beaten by soldiers. He discovered as well that the NCOs

of his battalion were seizing food from local villagers. On a few occasions,

he heard rumors around the camp about Burmese troops raping women and burning

villages during anti-insurgency campaigns in ethnic minority areas. Once he

was late for patrol and in his haste also forgot his rifle. For this offense,

his NCO beat him severely. “I just could not take it any more. I was

unhappy and homesick,” claimed Maung K. After three years in the army,

he decided to escape. He slipped away from his front line post and walked

to a Karen village about three hours away. “I turned myself over to the

villagers, and I waited there for the KNLA soldiers,” stated Maung K.

KNLA soldiers were surprised at the boy’s emaciated condition. Months

after his escape from the Burmese Army, a senior KNU official informed me:

“We never treated him as a prisoner, and he is not in captivity here.

Look at him. He has grown a lot since he has been here. When he first came

to us, he was really skinny.”

3. “I saw my father after the graduation ceremony (the first contact

he had with his family since his seizure by the army). He was sad and said,

“Lead a good life, son.”

Maung N

Age: 16

Ethnicity: Burman

Maung N holding UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (in Burmese language).

Muang N was seized at night with two of his friends as they were returning

from an evening tutorial class. He recounts his seizure:

“They (the soldiers) surrounded us and told us not to run. We were then

forced into a truck. I was scared. I did not know what was going to happen

to me.”

Maung N was immediately sent to a military training camp. He stated the majority

of training consisted of weapons maintenance, drill, and marching, with little

emphasis put on tactical, combat, or survival training. He speculated that

most of the recruits in his one thousand man training battalion were under

18 and primarily ethnic Burman. He often saw instructors strike recruits with

hands or sticks for making “small mistakes.” Maung N stated, “We

(boy soldiers) were very afraid. You could be beaten for the slightest mistake.”

Recruits that attempted to escape were subject to violent and prolonged beatings.

Maung N heard rumors that one the members of his recruit class died from injuries

after sustaining one of these beatings. After forced conscription, the first

contact Maung N had with his family was at his graduation ceremony from the

army. “We (the recruits) wrote letters in training and the instructors

collected them. But I do not think they were ever posted,” said Maung

N.

Upon arrival to his front line post, Maung N witnessed prisoner porters being

beaten, and was ordered to shoot them if they attempted to escape. He estimated

that thirty of the soldiers in his one hundred and fifty man battalion were

underage. Homesick and scared, he claimed that there was no one in the battalion

that he could talk to or rely on. Instead, he was expected to perform whatever

tasks were assigned to him and endure the hardships of his new life. Hunger,

exhausting labor, and mistreatment by his NCOs compelled Maung N to flee:

“I had to carry heavy bags of rice uphill. We worked all day long, and

it was only at night that we were given our rifles. I knew soon we were going

to build a new camp, and that meant building many fences. I could not take

it anymore.”

4. “I am a Buddhist. I do not want to kill.”

Maung A

Age: 15 (forcibly conscripted at age 14)

Ethnicity: Burman

Another fractured life: Maung A

Maung A was seized on the streets of his hometown by a Burmese Army sergeant

in uniform. That same day he was whisked away to a recruiting center, handed

a uniform, and was told by an instructor, “Now, you are a soldier. If

you try to run away, you will be shot.” During training, he heard rumors

that recruiters were being paid 5000 Kyat per new recruit they could “enlist.”

Maung A speculates that at least half of the members of his recruit company

were boys under the age of 16. He witnessed recruits being struck or beaten

by instructors for “making mistakes,” for example, during marches

or close order drill. Instructors told his recruit company that “rebel

groups” routinely committed rapes and murders, and would cut the throat

of any Burmese soldier taken prisoner. Maung A claims that recruits were not

fed adequately or given satisfactory medical care, “I was always hungry.”

He also heard rumors that three members of his recruit class died of tuberculosis

in the camp medical clinic.

At the front line in Karen state, he observed prisoner porters being beaten

by the Army. Although he was told by his NCOs that the porters were convicts,

he believes some of them were villagers. Under the weight of heavy, oversized

military equipment, Maung A performed each day ten hours of labor and assorted

military activities, in addition to night sentry duty. He was aware of the

difficulties faced by other boy soldiers in his front line battalion and stated,

“They were homesick and crying.” Maung A decided to flee from his

post and surrender to the Karen National Union due to a combination of emotional

and physical exhaustion, “I was overloaded. I was tired of the beatings

and the hard work.”

Plans for the Future

Maung Y: “I want to go home. I want to catch up on all the schooling

that I missed.”

Maung K: “I want to train to be a boxer.”

Maung N: “I want to go home. I also want to get job there, but I am afraid

I will never be able to return to my home village.”

Maung A: No plans.

Parties interested in providing relief for the subjects of this report should

contact: kawthule@yahoo.com

Closing note: The Thai agreement with the SPDC to return escaped child soldiers,

in the words of one border human rights worker, seals the fate of over 70,000

child soldiers, the vast majority of whom were press ganged into the Burmese

Army. This constitutes a formal commitment by the Thais to abuse human rights.